From Gold to Fiat: How the U.S. Dollar Changed — and What It Means for You

May 21, 2025

From Gold to Fiat: How the U.S. Dollar Changed — and What It Means for You

What Happened to the U.S. Dollar?

From Gold-Backed Currency to Fiat Control

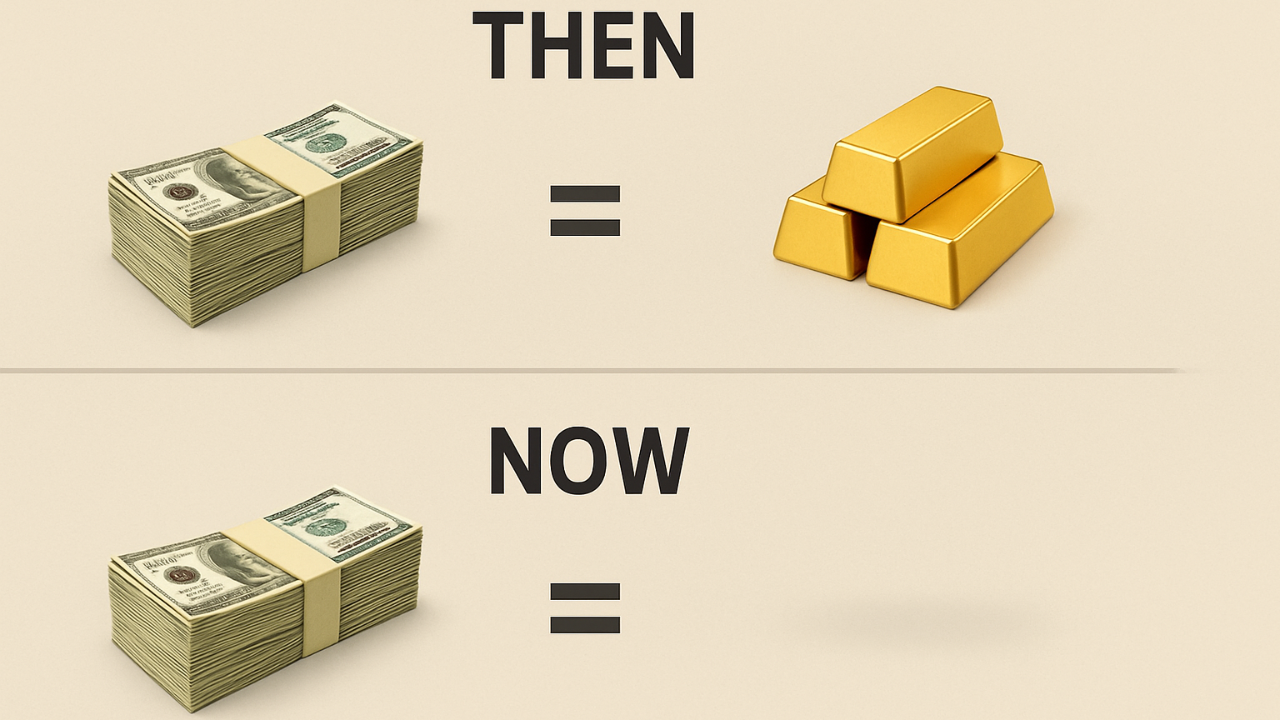

To understand why your money doesn’t stretch like it used to, you have to go back to the moment the definition of money changed. Not just the price of things, but the actual rules behind how dollars work.

This shift didn’t happen overnight. The U.S. rewrote the financial playbook — twice — giving the federal government full control over monetary policy, while quietly removing financial autonomy from everyday people.

First: Roosevelt Seizes Gold (1933)

During the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102, making it illegal for Americans to own large amounts of gold. Citizens had to hand their gold over to the government in exchange for $20.67 per ounce.

Why? At the time, the U.S. was on a gold standard, meaning every dollar had to be backed by a set amount of gold. But with banks failing and deflation (a general drop in prices that increases the value of debt) strangling the economy, the government needed more flexibility.

By seizing gold and then raising its official price to $35/oz, the federal government instantly devalued the dollar and expanded the money supply. That made it easier to pay off debts and stimulate growth (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 1933).

The move worked — economically. But it also set a precedent: in a crisis, your financial assets can be seized, revalued, or devalued — legally.

Private gold ownership wasn’t fully legal again until 1974.

Then: Nixon Abandons the Gold Standard (1971)

By the 1960s, the U.S. dollar was still tied to gold through the Bretton Woods system — a post-WWII global agreement that pegged international currencies to the dollar, and the dollar to gold at $35/oz.

But U.S. inflation was rising. The Vietnam War and social spending widened deficits. Countries like France began demanding actual gold in exchange for dollars. U.S. gold reserves began to shrink fast.

So in 1971, President Nixon “temporarily” suspended gold convertibility — ending Bretton Woods and turning the dollar into a fiat currency: backed by nothing but trust in the government. That “temporary” suspension was never reversed (Federal Reserve History, 1971).

Inflation Surge:

By 1980, inflation hit 13.5%. Studies show a near-perfect correlation (0.99) between fiat currency growth and inflation after 1971 (Preserve Gold, 2024).

Why Trust Matters:

Fiat currency only works if people believe in it. Nixon framed the move as protecting “the American worker” — but it shifted systemic risk to everyday households (CVCE, 1999).

From that moment on, money was no longer tied to something real. Its value came from policy, central banking, and public confidence.

Does the U.S. Still Have Gold Reserves?

Officially? Yes.

-

The U.S. holds the largest official gold reserve in the world:

261.5 million troy ounces (~8,133 metric tons)

Worth over $500 billion today

Stored at Fort Knox, the Denver Mint, and the New York Fed (U.S. Treasury, 2024)

But...

-

No full public audit of Fort Knox has been released in decades

-

Some claim gold has been sold off, pledged, or moved

-

There’s no proof the gold is gone — but no definitive proof it’s all still there either

Silver Coins: The Final Disconnect

It wasn’t just paper money that lost its backing.

Until 1964, U.S. coins like dimes, quarters, and half-dollars were made with 90% silver. These had real, metal-based value.

But as silver prices rose, people started hoarding and melting coins for profit. To stop this, Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1965, removing silver from most circulating coins and replacing it with copper-nickel blends.

By 1970, silver coins had mostly disappeared. This marked the final break between U.S. money and tangible value — in both paper and coin form.

From Pegged to Floating: The Rise of Fiat Currency

When Nixon severed the dollar’s tie to gold in 1971, the U.S. entered a new era: pure fiat currency.

Fiat means the money isn’t backed by anything physical. It gets value from government decree and public trust.

At first, Americans didn’t feel much change. The dollar looked the same. It spent the same. But under the surface, everything changed.

With no gold limit, the U.S. could print, spend, and inflate without restraint. Supporters said this flexibility helped fight recessions. Critics warned it would lead to unchecked debt and inflation.

They were right to worry.

Since 1971, the dollar has lost over 85% of its purchasing power (Federal Reserve, 2023).

What cost $1 in 1971 costs over $7.80 today.

Wages didn’t keep up. But costs — housing, education, healthcare — exploded.

Inflation: Built Into the System

The Federal Reserve now targets a 2% annual inflation rate.

That’s not a ceiling — that’s the goal.

This means prices are supposed to rise a little every year. The logic is:

-

People will spend instead of hoard cash

-

Borrowing becomes easier

-

The economy keeps moving

But here’s the reality:

2% inflation means your money’s value halves every 35 years.

If you’re 30 now, $100 today will only buy $50 worth of stuff by retirement — even if you did nothing wrong.

And when you hear inflation is “cooling,” it doesn’t mean prices are going down. It just means they’re going up more slowly.

Those price hikes you already felt? They’re baked in.

So Who Benefits From This?

-

The Government: Inflation shrinks the value of debt over time. A $1 trillion loan becomes easier to repay.

-

Asset Owners: Real estate and stocks tend to rise with inflation. Wealth grows.

-

Borrowers with Fixed Rates: A 30-year mortgage doesn’t go up, even as wages (hopefully) rise.

But who loses?

-

Savers: Especially if their money sits in low-interest accounts

-

Wage Earners: If their income doesn’t keep pace with rising costs

-

Those Without Assets: Everything costs more, but they own nothing that gains value

From Gold to Debt: What Really Backs the Dollar Now

Since 1971, the dollar has been backed by one thing: debt.

When you use a credit card, take out a car loan, or get a mortgage, new dollars are created in the banking system.

Banks don’t need to keep all your money. They lend most of it out again and again — a process called fractional reserve banking.

That means:

The more we borrow, the more money exists.

Debt isn’t just a tool anymore. It’s the engine of the entire economy.

If borrowing slows down too much? Growth stalls. Recession risk rises.

That’s why central banks lower interest rates during downturns — to get people borrowing again.

The U.S. Debt Today

-

1933 (FDR’s gold recall): ~$22 billion

-

1944 (Bretton Woods): ~$204 billion

-

1971 (End of gold standard): ~$398 billion

-

2024: Over $34 trillion (U.S. Treasury, 2024)

Household debt has passed $17 trillion, including credit cards, student loans, and auto loans (Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2024).

Even corporations are deep in debt — often borrowing to buy back stock or stay afloat.

And interest payments on the national debt are now competing with the defense budget.

Why This Matters — and What You Can Do

If you’ve ever felt like you’re working harder but getting less, you’re not wrong.

We now live in a system where dollars are created from debt, where inflation is planned, and where your money is designed to lose value over time.

Prices aren’t just high — they’re meant to keep rising. Wages don’t just lag — they’re not built to keep up. And saving cash in a bank account isn’t safe — it’s quietly losing value every day.

These aren’t accidents. They’re features of the system. And that means your approach to money can’t be business as usual.

So what can you do?

-

Start insulating yourself financially. That means building a buffer — based on how you want to live and what you want to leave behind.

-

Diversify your income streams. So one job loss doesn’t derail your entire life.

-

Own something. Anything. Whether it’s a side business, land, or even intellectual property — assets matter more than cash.

-

Stack value where you can. That might mean savings, real estate, skills, or paying off debt — all of it counts.

-

Understand the System. So you don’t just react to trigger words and phrases — you strategize with intention and understanding.

When the U.S. moved from a gold-backed currency to a fiat-based system, it didn’t just change the composition of money — it redefined how the economy functions. Dollars are now created through debt, inflation is an intentional feature, and long-term purchasing power depends less on saving and more on navigating the system strategically.

For individuals, this shift raises important questions:

-

What does it mean to preserve value in a system designed for gradual loss?

-

How do debt, ownership, and inflation affect long-term stability?

-

What tools are still effective — and which may be outdated?

There is no one-size-fits-all answer. But understanding the history and structure of the monetary system is the first step toward making informed financial decisions.

If this blog gave you insight, the community will give you depth and strategy.